I've been thinking about this a lot lately as I watch the latest round of federal interoperability pledges make their way through the health care trade press. The headlines are predictable: "Major Health Systems Commit to Data Sharing," "Tech Giants Promise Open Standards," "White House Announces Breakthrough Initiative."

But here's the thing—I've seen this movie before.

Multiple times.

And I’m starting to think we’re all wasting our time on what amounts to political theater while the real work of health care transformation happens elsewhere.

Let me explain using a framework I've been applying to evaluate where to spend my limited attention: the sizzle vs. substance matrix.

The Sizzle vs. Substance Problem

Consider a simple 2x2 matrix. On the horizontal axis, you have substance—actual impact, measurable outcomes, lasting change. On the vertical axis, you have sizzle—visibility, media attention, political appeal, the stuff that gets people excited at conferences.

I'm a Quadrant 4 kind of guy. I want to spend my time on important things that aren't necessarily urgent (invoking Covey a bit here, I suppose). Optimizing health IT systems, improving clinical workflows, building better data infrastructure—that's Quadrant 4 work.

Interoperability pledges? They're textbook Quadrant 1.

A Brief History of Promises

A Brief History of Promises

The Original Blue Button: Carol Diamond's Vision Meets Reality

The story really starts with Carol Diamond @ the Markle Foundation and the original Blue Button initiative around 2009. What if patients could simply click a blue button on any health care website and download their health data? Simple, universal, empowering.

The concept was brilliant in its simplicity. Veterans Affairs launched the first Blue Button in 2010, allowing veterans to download their health records as text files. It was a genuine innovation—the first large-scale effort to give patients direct access to their own data. Other federal agencies followed: Medicare, Medicaid, even the Department of Defense.

But here's where the pattern emerges: the voluntary Blue Button Pledge that followed in 2011-2012 generated lots of enthusiasm and over 600 organizational commitments, but minimal real-world adoption. Health plans and providers signed up to show they cared about patient engagement, but implementation was spotty at best, and the user experience was often terrible.

What actually worked: When CMS launched Blue Button 2.0 in 2018 with a working FHIR API providing access to Medicare claims data for over 53 million beneficiaries, suddenly everyone discovered the value of patient data access. Not because of the pledge, but because CMS built the infrastructure and made it available.

The Early Days: Good Intentions, Limited Impact

ONC's first decade (2004-2014) was filled with well-intentioned voluntary initiatives that followed this same pattern. The Nationwide Health Information Network (NHIN) launched in 2006 as a voluntary network of networks approach to health information exchange. Great concept, limited adoption.

The Health Information Security and Privacy Collaboration (HISPC) brought together states to develop voluntary privacy and security practices for health information exchange. Valuable work, but it didn't drive widespread HIE adoption.

Even the early Regional Health Information Organizations (RHIOs) were largely voluntary collaboratives. Most failed or struggled until they found sustainable business models—usually involving some form of regulatory requirement or financial incentive.

I remember the optimism of those early years. We genuinely believed that if we just built the right voluntary frameworks, demonstrated the value, and got everyone to sign on, interoperability would naturally follow. The American Health Information Community (AHIC) recommendations, the Connecting for Health collaborative, the various workgroups and committees—all focused on building consensus and voluntary adoption.

The Meaningful Use Turning Point

The real transformation began with the HITECH Act in 2009 and the Meaningful Use program that followed. Suddenly, instead of asking nicely for EHR adoption and interoperability, we were offering billions in Medicare and Medicaid incentives—with penalties for non-compliance.

Stage 1 Meaningful Use (2011) required basic EHR functionality and some limited data exchange capabilities. Stage 2 (2014) pushed harder on interoperability, requiring providers to enable patient access to their data and demonstrate some level of health information exchange.

The results were dramatic: EHR adoption went from roughly 10% of hospitals in 2008 to over 95% by 2015. Patient portal availability jumped from virtually nothing to standard practice. Health information exchange, while still imperfect, became a real thing rather than a conference topic.

The Pattern Emerges

Looking back at that first decade of ONC's work, the pattern is unmistakable: voluntary initiatives generated awareness and built relationships, but regulatory requirements drove adoption. The Blue Button Pledge got people talking about patient data access, but Blue Button 2.0 made it real. The NHIN created a framework for health information exchange, but Meaningful Use Stage 2 made it happen.

This isn't a criticism of those early efforts—they were necessary steps in building the foundation for what came later. Carol Diamond's Blue Button vision was absolutely right; it just took regulatory backing to make it work at scale. The NHIN architecture informed everything that followed, including TEFCA.

But it does illustrate why I've become skeptical of pledge-based approaches. We've been down this road before, many times. The voluntary phase generates enthusiasm and builds consensus, but the transformation phase requires accountability and consequences.

The 2016 HIMSS Pledge: All Sizzle, No Substance

Remember February 2016? HHS Secretary Sylvia Burwell stood on stage at HIMSS and got 17 EHR vendors (representing about 90% of the hospital market) to pledge they'd stop information blocking and embrace open standards. The American Hospital Association signed on. The American Medical Association signed on. It was a big moment.

Outcome: Nothing measurable happened.

What actually worked: Later that year, Congress passed the 21st Century Cures Act, which made information blocking illegal and mandated FHIR-based APIs. Suddenly, everyone discovered religion about interoperability—not because of their pledge, but because the law required it.

The VA API Pledge: Good Intentions, Regulatory Reality

In March 2018, the Department of Veterans Affairs organized another pledge. Cerner, Epic, and major health systems committed to implementing open FHIR APIs for veteran data sharing. It sounded great.

Outcome: Some progress on FHIR standardization, but the real gains came from the VA's massive EHR modernization contract with Cerner and federal oversight—not the voluntary commitments.

Big Tech's Interoperability Moment: Symbolic Gestures

The Trump administration got Amazon, Google, IBM, Microsoft, Oracle, and Salesforce to pledge support for open standards and API adoption in 2018 and 2019. Tech companies backing interoperability—what's not to love?

Outcome: Companies developed some open tools and publicly supported CMS/ONC rules, but industry-wide FHIR adoption only happened after CMS and ONC finalized their regulations in 2020 requiring payers and EHRs to support FHIR-based APIs.

What Actually Moves the Needle

While pledge ceremonies were generating headlines, the real work was happening in the regulatory trenches—classic Quadrant 4 territory.

The HITECH Act (2009)

No fanfare, just a law that created the Meaningful Use program and tied EHR adoption to Medicare and Medicaid incentives. Result: EHR adoption went from virtually nothing to over 96% of hospitals in a few years.

Meaningful Use Stage 2 (2014)

Required providers to enable patient online access to health data. Result: Patient portal availability jumped from 43% to 89% of hospitals in one year.

The 21st Century Cures Act (2016)

Made information blocking illegal and required open, FHIR-based APIs from certified EHRs. Result: Enabled all the subsequent interoperability progress we've actually seen.

CMS & ONC Interoperability Rules (2020)

Required certified health IT to support FHIR APIs and mandated that payers provide member data via APIs. Result: By 2022, over 90% of hospitals had enabled API access, with about 67% using FHIR.

Every single meaningful advance in interoperability has followed the same pattern: regulation drives adoption, not voluntary commitments.

The 2025 Pledge

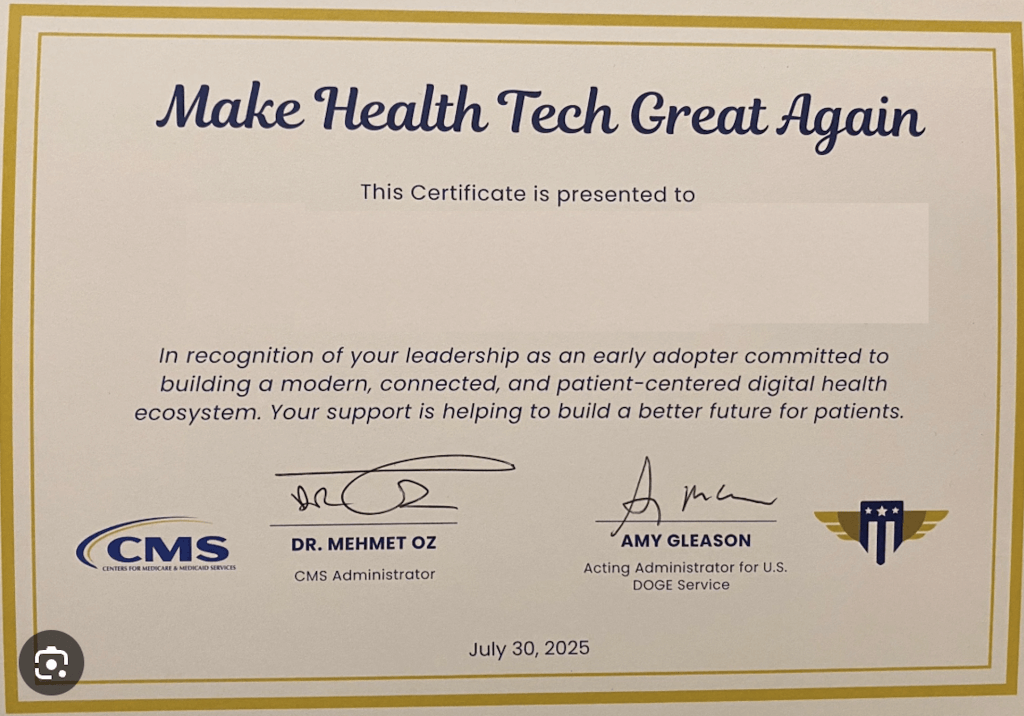

So here we are in 2025, and CMS and the White House have organized another pledge. EHR vendors promise to "kill the clipboard." Twenty-one health information exchanges commit to adopting new CMS interoperability frameworks. AI and digital identity companies pledge to deliver new tools.

I'm sure it will generate great headlines. I'm equally sure it won't move the needle—at least not until CMS backs it up with regulatory requirements or financial incentives.

Why This Matters

Here's my concern: pledges aren't just ineffective—they're counterproductive. They create the illusion of progress while delaying the regulatory action that actually works. They let organizations claim they're "committed to interoperability" while continuing practices that impede data sharing. They waste the limited attention and political capital we have for health care transformation.

I spent three years at ONC—first as Chief Medical Officer under Farzad Mostashari, then as Deputy National Coordinator under Karen DeSalvo, and briefly as Acting National Coordinator between them. Those were some of the best years of my professional life, working with dedicated people aligned around a shared goal of better health for millions of Americans.

What I learned there is that change moves at the speed of trust (Farzad should be credited with coining this tem) —but it also moves at the speed of accountability. Voluntary pledges provide neither trust nor accountability. They provide political cover.

The Quadrant 4 Alternative

So what should we be doing instead? Focus on the important but not urgent work that actually creates lasting change:

Regulatory Intelligence: Develop systematic processes for tracking regulatory developments, analyzing their implications, and preparing for implementation. This infrastructure investment pays dividends across multiple regulatory cycles.

Implementation Excellence: Rather than seeking visibility through pledge participation, prioritize exceptional execution of regulatory requirements. This builds competitive advantage while advancing substantive interoperability goals.

Technical Leadership: Invest in technical capabilities that exceed regulatory minimums. Build FHIR implementations that actually work. Create APIs that developers want to use. Focus on patient outcomes rather than compliance checkboxes.

Stakeholder Engagement: Participate meaningfully in regulatory comment periods. Engage with ONC and CMS during rule development. Build relationships with the people doing the actual work of health care transformation.

This is Quadrant 4 work—low sizzle, high substance. It doesn't generate conference buzz or trade press coverage. But it's where the real transformation happens.

I'm not saying pledges are evil—they're just not where the action is. And life is too short to spend it in Quadrant 1 when there's so much Quadrant 4 work to be done.

The next time you see a headline about a major interoperability pledge, ask yourself: Is this sizzle or substance? Then decide accordingly.

Because while everyone else is making promises, the real work of health care transformation will be happening in the regulatory trenches, one FHIR implementation at a time.